Econometrics - Theories, Models, and Functions

- Description

- Curriculum

- FAQ

- Reviews

Introduction to Econometrics

This course will cover material comparable to a typical first course in econometrics. It includes 27 hours of 100 easy-to-understand lectures with over a hundred downloadable PDF resources accompanying the lectures.

This course will cover:

Chapter 1: The algebra of least squares with one explanatory variable

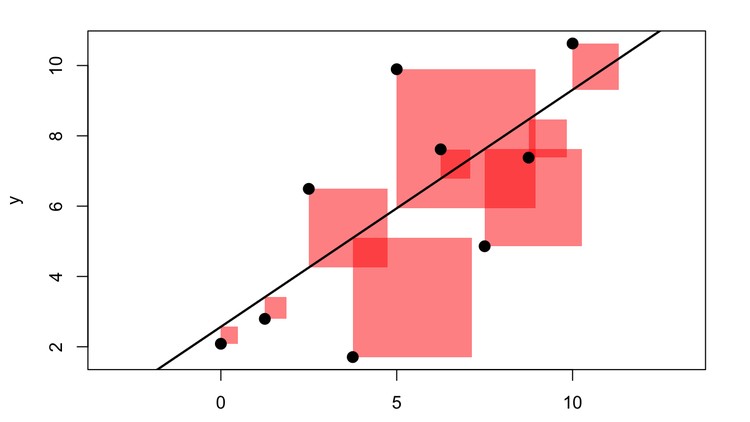

This chapter introduces the least squares method which is used to fit a straight line through a scatter plot. This chapter focuses on the algebra of least squares. There is no probability theory or statistics in this chapter. The chapter begins with sample moments, goes through and derives the OLS formula. Important concepts introduced in this chapter: Trendline, residuals, fitted values and R-squared. In addition to Excel, we will also introduce EViews in this chapter and look at how to find trendlines using Excel and EViews.

Chapter 2: Introduction to probability theory

In order to make more sense of the concepts introduced in chapter 1, we need some probability theory and statistics. We want to be able to explain observed deviations from the trendline and we will do that with random variables called error terms. This chapter covers the absolute minimum from probability theory: random variables, distribution functions, expected value, variance and covariance. This chapter also introduces conditional moments which will turn out to be of great importance in econometrics as the fundamental assumption on the error terms will be stated as a conditional expectation.

Chapter 3: The linear regression model with one explanatory variable

This chapter formalizes the most important model in econometrics, the linear regression model. The entire chapter is restricted to a special case, nameley when you have only one explanatory variable. The key assumtion of the linear regression model, exogeneity is introduced. Then, the OLS formula from chapter 1 is reinterpreted as an estimator of unknown parameters in the linear regression model. This chapter also introduces the variance of the OLS estimator under an important set of assumptions, the Gauss-Markov assumptions. The chapter concludes with inference in the linear regression model, specifically discussing hypothesis testing and confidence intervals.

Chapter 4: The regression model with several explanatory variable

This chapter is an extension of chapter 3 allowing for several explanatory variables. First, the linear regression with several explanatory variables, the focus of this chapter, is thoroughly introduced and an extension of the OLS formula is discussed. Since we are not using matrix algebra in this course, we will not be able to present the general formulas such as the OLS formula. Instead, we rely on the fact that they have been correctly programmed into software such as Excel, EVies, Stata and more. We need to make small changes to the inference of this model and we will also introduce some new tests. A new problem that will appear in this model is that of multicolinearity. Next, we look at some nonlinear regression models followed by dummy variables. This chapter is concluded with an anlysis of the data problem heteroscedasticity.

Chapter 5: Time series data

This chapter is an introduction to econometrics with time series data. Chapters 1 to 4 have been restricted to cross sectional data, data for individuals, firms, countries and so on. Working with time series data will introduce new problems, the first and most important being that time series data may be nonstationary which may lead to spurios (misleading) results. However, this chapter will only look at stationary time series data. Time series models may be static or dynamic, where the latter maeans that the dependent variable may depend on values from previous periods. We will look at some dynamic models, most importantly ADL (autoregressive distributed lag) models and AR (autoregressive) models. Another problem with time series data is that the error terms may be correlated over time (autocorrelation). The chapter concludes with a discussion of autocorrelation, how to test for autocorrelation and how to estimate models in the presence of autocorrelation.

Chapter 6: Endogeneity and instrumental variables

Throughout the course so far, we have assumed that the explanatory variables are exogenous. This is the most critical assumption in econometrics. In this chapter we will look at cases when explanatory variables cannot be expected to be exogenous (we then say that they are endogenous). We will also look at the consequence of econometric analysis with endogenous variables. Specifically, we will look at misspecification of our model, errors in variables and the simultaneity problem. When we have endogenous variables, we can sometimes find instruments for them, variables which are correlated with our endogenous variable but not with the error term. This opens for the possibility of consistently estimate the parameters in our model using the instrumental variable estimator and the generalized instrumental variable estimator.

Chapter 7: Binary choice models

This chapter is an introduction to microeconometric models. We will look at the simplest of these types of models, the binary choice model, a model where your dependent variable is a dummy variable. It turns out that we can use the same methods described in chapter 4, the model is then called the linear probability model. However, the linear probability model has some problems. For example, predict probabilities may be less than zero and/or larger than 100%. In order to rectify this problem, new models are presented (the probit- and the logit model) and a new technique for estimating these models is introduced (maximum likelihood).

Chapter 8: Non-stationary time series models

In chapter 5 working with time series data, stationarity was a critical assumption. In this chapter we investigate data that is not stationary, the consequences of using non-stationary data and how to determine if your data is stationary.

Chapter 9: Panel data

Panel data is data over cross-section as well as time. This chapter is only an introduction to models using panel data. The focus of this chapter is on the error component model where we look at the fixed effect estimator as well as the random effects model. The chapter concludes with a discussion of how to choice between s and how to choice between the fixed effect estimator and the random effects estimator (including the Hausman test).

-

1Sample momentsVideo lesson

This chapter introduces the least squares method which is used to fit a straight line through a scatter plot. This chapter focuses on the algebra of least squares. There is no probability theory or statistics in this chapter. The chapter begins with sample moments, goes through and derives the OLS formula. Important concepts introduced in this chapter: Trendline, residuals, fitted values and R-squared. In addition to Excel, we will also introduce EViews in this chapter and look at how to find trendlines using Excel and EViews.

Sample moments:

The first thing we will look at in this course is sample moments. We begin with concepts such as population, sample and random sample. First, we look at moments from a single varibale: sample mean, sample variance and sample standard deviation. We then look at sample moments from two variables: sample covariance and sample correlation. This section is heavily dependent of sums and you practice working working sums mathematically as well as in Excel.

-

2Introduction to EviewsVideo lesson

A brief introduction to EViews using both the menu system and commands. Introduces series and groups, sample moments, graphs and important commands.

Workbooks

Menus and commands

Pages

Structure of a page

Range and sample

Series type

Edit data

Group type

Sample moments: variance, covariance and correlation

Working with Excel

-

3Introduction to Commands in EviewsVideo lesson

Create a workfile. Example: wfcreate(wf=wf1) u 6 (unstructured, 6 observations)

Create a series with random numbers: series s1 = rnd

Create a series going from 1 to n: series s1 = @trend

Line graphs: s1.line or line s1 s2

Scatter plot: scat s1 s2

xy line plot: xy s1 s2

Create a scalar type: scalar c1

Assigning an element of a series to a scalar: c1 = s1(3) or c1 = @elem(s1,”3”) or c1 = @elem(s1,”2010:1”)

Operators and functions: Command and Programming references chapter 13

Show command. Example: show log(s1)

Special functions: @round, @mean, @sum

Normal distribution: @dnorm, @cnorm, @qnorm and @rnorm

Introduction to programs

-

4The OLS formulaVideo lesson

Ordinary least squares

This section introduces the OLS formula, the formula we use to find a straight trend line through a scatter plot. In this section, the formula is presented without any derivation. We will also look at how to find trend lines in EViews and Excel. Once we have our scatter plot and trendline, we can define residuals and fitted values. Using the residuals, we can introduce the least squares principle, the principle behind the OLS formula. Finally, we look at the special case when the intercept of our trend line is zero ("no intercept").

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture. -

5Introduction to equations in EviewsVideo lesson

Summary

Reordering series in a group

Scatter plot

Adding a trendline to a scatter plot

The equation object

Equations specification. Example: eval gpa c. eval is the depenedent variable, gpa the explanatory variable and c represents an intercept

Naming an equation

Creating an equation from the command window. Example: ls eval gpa c or equation eq01.ls eval gpa c

The representation view

Estimation output view

Understanding the output

@coefs function for estimated parameters. Example: scalar c = @coefs(1)

Object reference. Chapter 1: Equation

-

6Residuals and fitted valuesVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

7The least squares principleVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

8Trendline with no interceptVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

9Deriving the OLS formulaVideo lesson

Deriving the OLS formula

This section presents the least squares principle mathematically as a minimization problem in two variables (intercept and slope). We will solve this problem analytically which will result in the OLS formula. Based on the first order condition from the optimization problem, we can derive several important OLS results.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

10Global minimum of RSSVideo lesson

-

11Some OLS resultsVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

12Measure of fitVideo lesson

In some cases, our trendline will fit our data well and in some cases it will not. In order to derive a measure of fit, we begin by identify an important result: the total variation in the data will be equal to the variation that we can explain (with the trend line) and variation that we cannot explain. From this, we define the measure of fit, R-squared, as the proportion of the total variation that we can explain.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

13Residuals and fit in EviewsVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

14Random variableVideo lesson

In order to make more sense of the concepts introduced in chapter 1, we need some probability theory and statistics. We want to be able to explain observed deviations from the trendline and we will do that with random variables called error terms. This chapter covers the absolute minimum from probability theory: random variables, distribution functions, expected value, variance and covariance. This chapter also introduces conditional moments which will turn out to be of great importance in econometrics as the fundamental assumption on the error terms will be stated as a conditional expectation.

Random variables and distributions

The most fundamental concept in probability theory is the random variable. We will not be able to analyze the formal definition of a random variable as this is very technical. However, we will be able to develop an understanding of a random variable and this is all we need. It will turn out to be useful to distinguish between discrete random variables and continuous random variables. Random variables are intimately connected to their distribution functions and this will be discussed in detail. Finally, we look at a specific random variable, the standard normal random variable. The standard normal has the well known bell-shaped density function.

-

15Distribution functionsVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

16Standard normalVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resources for this lecture.

-

17Expected value of a discrete random variableVideo lesson

Moments of a random variable

Once we know what a random variable is, we will look at important properties of a random variable. Most important are its expected value and its variance. We will look the definitions as well as the intuition behind these properties. Next, we can create a new random variable from an old one. If the new one is a linear function of the old one, then figuring out its expected value and variance is particularly simple. We end this section with the normal random variables which may have any expected value and any positive variance.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

18Expected value of a continuous random variableVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

19The variance of random variableVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

20The expected value and variance of a linear function of a random variableVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

21Normal distributionVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

22Covariance, correlation, and independence (intro)Video lesson

Moments of two or more random variables

In the previous section we looked at a single random variable and its moments. In this section we will look at several random variables and the combined moments of two of them. First, we look at covariance, correlation and independence. Then, we look at conditional expectation and the conditional variance of one random variable given another. We end this section by looking at a sequence of random variables introducing the concept random sequence of random variables meaning that all the random variables in this sequence or independent and have the same distribution.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

23Conditional expectation and conditional variance, introductionVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

24Sample as a sequence of random variablesVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

25The linear regression modelVideo lesson

This chapter formalizes the most important model in econometrics, the linear regression model. The entire chapter is restricted to a special case, nameley when you have only one explanatory variable. The key assumtion of the linear regression model, exogeneity is introduced. Then, the OLS formula from chapter 1 is reinterpreted as an estimator of unknown parameters in the linear regression model. This chapter also introduces the variance of the OLS estimator under an important set of assumptions, the Gauss-Markov assumptions. The chapter concludes with inference in the linear regression model, specifically discussing hypothesis testing and confidence intervals.

The linear regression model

The first section of this chapter is devoted to describing the linear regression model. In the linear regression model a dependent variable is explained partly as a linear function of an explanatory variable and partly by an error term. The parameters of the linear function, the beta parameters, are viewed as unknown. If we estimate these parameters using the OLS formula then we have what is called the OLS estimator.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

26LRM with an exogenous explanatory variableVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

27The OLS estimatorVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

28When are the OLS estimators unbiased and consistent?Video lesson

The properties of the OLS estimator

in order to evaluate the usefulness of an estimator, we introduced to properties held by good estimators, unbiasedness and consistency. It turns out that the OLS estimator has favorable properties as long as the explanatory variable is exogenous. However, it is possible to find many different estimators with these properties. Therefore, we need some method of distinguishing between them. To do that, we begin by assuming that the error terms are homoscedastic, that is, they all have the same variance. With this assumption, we can find the variance of the OLS estimators and show that the OLS estimator has the lowest variance among all linear unbiased estimators. This result is called the Gauss Markov theorem.

-

29Homoscedasticity, heteroscedasticity and the Gauss-Markov assumptionsVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

30The variance of the OLS estimatorVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

31Estimating σ2Video lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

32Estimating the variance of the OLS estimatorsVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

33The Gauss-Markov theoremVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

34The chi-square distributionVideo lesson

Some distributions

In order to prepare for the final section of this chapter, the section dealing with inference in the linear regression model, we need to discuss a couple of families of random variables. Specifically, we will look at the chi-square distribution, the t-distribution, and the F distribution and we will also look at the concept critical value.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

35The t-distributionVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

36The F-distributionVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

37Critical valuesVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

38Introduction to hypothesis testingVideo lesson

Inference in the linear regression model

this section is an introduction to inference in the linear regression model. We will begin by looking at hypothesis testing as a general idea in statistics followed by hypothesis testing in the linear regression model. In this section we will only look at the t-test where we test if one of the unknown parameters is equal to some given value. Hypothesis testing is closely related to confidence intervals and we will look at confidence intervals for the beta parameters of the linear regression model.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

39Hypothesis testing in the LRM: The t-testVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

40Confidence intervals in the LRMVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

41Linear regression with several explanatory variablesVideo lesson

The regression model with several explanatory variable

This chapter is an extension of chapter 3 allowing for several explanatory variables. First, the linear regression with several explanatory variables, the focus of this chapter, is thoroughly introduced and an extension of the OLS formula is discussed. Since we are not using matrix algebra in this course, we will not be able to present the general formulas such as the OLS formula. Instead, we rely on the fact that they have been correctly programmed into software such as Excel, EVies, Stata and more. We need to make small changes to the inference of this model and we will also introduce some new tests. A new problem that will appear in this model is that of multicolinearity. Next, we look at some nonlinear regression models followed by dummy variables. This chapter is concluded with an anlysis of the data problem heteroscedasticity.

The linear regression model with several explanatory variables

We begin this chapter by extending the linear regression model allowing for several explanatory variables. For example, if we have three explanatory variables then, including the intercept, we will have four unknown beta parameters. We will use the symbol k to denote the number of unknown beta parameters. The OLS principle for estimating the beta parameters will still work but the mathematics will become more complicated and is best done using matrices. However, we can always feed data into software and get the OLS estimates from the software. The fundamental assumption introduced in chapter 3, exogeneity, will be discussed and we will conclude that the OLS estimator will be unbiased and consistent under this assumption. Further, the OLS estimator will be best if the error terms are homoscedastic.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

42OLSVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

43The properties of the OLS estimatorVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

44Hypothesis testing, one restriction – the t-testVideo lesson

Inference in the linear regression model with several explanatory variables

We begin by looking at the t-test which we use to test a single restriction. In a linear regression model with several explanatory variables it is common to consider hypotheses involving several restrictions. Such hypotheses can be tested using an F test. Finally we look at confidence intervals when we have many explanatory variables.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

45Hypothesis testing, several restrictions – the F-testVideo lesson

-

46Confidence intervals in the LRMVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

47MulticollinearityVideo lesson

Multicollinearity and forecasting

This section contains two unrelated topics. We begin by looking at multicollinearity, a problem where the explanatory variables are highly correlated. Presence of multicollinearity makes it difficult to estimate individual beta parameters. Forecasting will allow us to predict the value of the dependent variable for given values of the explanatory variables even when the observation is not part of our sample.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

48Forecast in the LRMVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

49Linear in parameters and/or linear in dataVideo lesson

Nonlinear regression model

So far, the dependent variable has been modeled as a linear function of the explanatory variables plus an additive error term. In this section, we will look at nonlinear models. It turns out that we have two types of linearity in the linear regression model. First, the dependent variable is linear in the explanatory variables. Second, the dependent variable is linear in the beta parameters. Therefore, we can consider two types of non-linearity. In this section, we will focus mainly on nonlinearity in the explanatory variables retaining linearity in the parameters. We will then look at the most common nonlinear models, the log-log model, the loglinear model and a model where we only log (some of) the x variables. Once we have an nonlinear model, we need to reinterpret the beta parameters. For example, in the log-log model, the beta parameters will be elasticities. Choosing between a linear regression model and a model nonlinear in the explanatory variables can be difficult. To help us in this choice, we introduce Ramsey’s RESET test.Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

50Linear regression models which are nonlinear in dataVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

51The log-log modelVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

52The log-linear modelVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

53Logging an x-variableVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

54Ramsey’s RESET testVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

55The LRM with a dummy variableVideo lesson

Dummy variables

If all observations belong to one out of two groups, then a dummy variable can be used to encode this information. A dummy variable will take the value zero for all observations belong to one group and one for all the remaining observations belonging to the other group. We can use a dummy variable as an explanatory variable in a linear regression model in the same way that we use an ordinary explanatory variable. Dummy variables can be used even if you have more than two groups.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

56LRM with more than two categoriesVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

57Interactive dummy variablesVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

58The Chow testVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

59HeteroscedasticityVideo lesson

Heteroscedasticity

Heteroscedasticity means that the variance of the error term is different between different observations and this is very common in economics. We begin by looking at tests helping us figuring out if our data is homoscedastic or heteroscedasticity. If we find that we have heteroscedasticity, then the standard errors derived by assuming homoscedasticity are no longer valid. Instead, we can use robust standard errors. Also, with heteroscedasticity OLS is no longer efficient. In this case, the efficient estimator is called the weighted least squares.

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

60Test for heteroscedasticity using squared residualsVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

61Robust standard errors with heteroscedasticityVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

62Weighted least squaresVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

63Time series dataVideo lesson

This chapter is an introduction to econometrics with time series data. Chapters 1 to 4 have been restricted to cross sectional data, data for individuals, firms, countries and so on. Working with time series data will introduce new problems, the first and most important being that time series data may be nonstationary which may lead to spurios (misleading) results. However, this chapter will only look at stationary time series data. Time series models may be static or dynamic, where the latter maeans that the dependent variable may depend on values from previous periods. We will look at some dynamic models, most importantly ADL (autoregressive distributed lag) models and AR (autoregressive) models. Another problem with time series data is that the error terms may be correlated over time (autocorrelation). The chapter concludes with a discussion of autocorrelation, how to test for autocorrelation and how to estimate models in the presence of autocorrelation.

Static time series models

With time series data it is no longer reasonable to assume that our sample is a random sample. For example, inflation in this period tends to be correlated with inflation in the previous period. Instead, it may be reasonable to assume that our time series data is stationary. In this section you will learn more about the stationary the assumption. We also need to modify the Gauss Markov assumptions such that OLS is unbiased, consistent and efficient under these assumptions.

-

64StationarityVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

65LRM with time series data – the static modelVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

66The properties of the OLS estimator in the static modelVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

67ADL(p,q) modelVideo lesson

Dynamic time series models

In this section we move onto dynamic time series models. By that we mean that we allow for lagged variables, the value of a variable from an earlier period. We may use lagged explanatory variables as well as lags of the dependent variable as additional explanatory variables. Such a model is called an autoregressive distributed lag model. We will then more carefully study a special case and a simpler model, namely the autoregressive model of order one. This is a simple model where the dependent variable depends on its value in the previous period and an error term. We extend this model to a more general autoregressive model where the dependent variable may depend on its value p periods back in time. We are then ready to go back and discuss estimation of the more general ADL model and we can identify the long run and the short run effects of a change in one of the explanatory variables.

-

68The AR(1) processVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

69The AR(p) processVideo lesson

The AR(p) process

-

70Estimating ADL(p,q) modelsVideo lesson

-

71Long run and short run effects in ADL modelsVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

72AutocorrelationVideo lesson

Autocorrelation

By autocorrelation in a regression model, we mean that the error term in this period depends on its value in previous periods. We will begin by looking at the Breusch-Godfrey test for autocorrelation. If we find that autocorrelation is present then the standard errors from OLS are no longer useful and we will look at robust standard errors. If it can be assumed that the error terms follow an AR(1) process, then it is possible to replace OLS with an efficient estimator.

-

73Test for autocorrelation, Breusch-Godfrey testVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

74Robust standard errors with autocorrelationVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

75Efficient estimation with AR(1) errorsVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

76Redundant variablesVideo lesson

Throughout the course so far, we have assumed that the explanatory variables are exogenous. This is the most critical assumption in econometrics. In this chapter we will look at cases when explanatory variables cannot be expected to be exogenous (we then say that they are endogenous). We will also look at the consequence of econometric analysis with endogenous variables. Specifically, we will look at misspecification of our model, errors in variables and the simultaneity problem. When we have endogenous variables, we can sometimes find instruments for them, variables which are correlated with our endogenous variable but not with the error term. This opens for the possibility of consistently estimate the parameters in our model using the instrumental variable estimator and the generalized instrumental variable estimator.

-

77Missing variablesVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

78Measurement errorsVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

79A simple model of measurement errors in a LRMVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

80Simultaneous equationsVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

81Simultaneous equation biasVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

82Endogenous variablesVideo lesson

-

83Instrumental variables, one explanatory variableVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

84Instrumental variables, several explanatory variablesVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

85Generalized IVVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

86Hausman test for endogenous variablesVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

87The linear probability modelVideo lesson

This chapter is an introduction to microeconometric models. We will look at the simplest of these types of models, the binary choice model, a model where your dependent variable is a dummy variable. It turns out that we can use the same methods described in chapter 4, the model is then called the linear probability model. However, the linear probability model has some problems. For example, predict probabilities may be less than zero and/or larger than 100%. In order to rectify this problem, new models are presented (the probit- and the logit model) and a new technique for estimating these models is introduced (maximum likelihood).

-

88Binary choice modelsVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

89Binary choice models, inferenceVideo lesson

Please download the PDF resource for this lecture.

-

90The problem with nonstationary dataVideo lesson

Summary

Main point from the lecture: If you run a regression yt=β1+β2xt+εtyt=β1+β2xt+εt using nonstationary data, you may end up with a spurious regression .

External Links May Contain Affiliate Links read more